Documentation of students in the main weaving studio at the Łódż Academy of FIne Arts, working on war nets for the Ukrainian war front in March, 2022. Photo: Marcin Stępień for Agencja Wyborcza.pl

Community through Camo:

Weaving War Nets for the Ukrainian Front

By Paulina Berczynski

Since the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian War, thousands of volunteers and war refugees in Ukraine, Poland, and other European nations have contributed their labor to make hand-woven camouflage nets for Ukrainian soldiers.

In March of 2023 I visited a community of textile artists in Łódź, Poland, who are creating nets to send to their neighboring country. These current actions build upon a weaving effort that started in 2014 during the Russian separatist attack on the Donbas region of Ukraine, and the annexation of Crimea. Whereas the work was initially contributed to exclusively by community groups of Ukrainian women, who worked on the nets “pretty much every day except Sundays”1, the project has grown to an international scale since the start of the 2022 Russian invasion. The day after the Russian attack, impromptu weaving “factories” began to spring up in spaces ranging from armories and library basements to traditional art spaces such as studios, galleries, and museums.

Students and faculty cutting fabric and weaving nets during a community work day. Courtesy of the group Polish Textile Art / Polska Sztuka Włókna-Tkanina, Facebook. March 2, 2022.

The process begins with donated fabric and clothing which is sorted by color and cut into strips. These strips are then woven by hand onto vertically hung square-mesh netting such as safety netting or repurposed volleyball and soccer nets. The finished nets are then sent off to the troops, who commission them to address specific wartime needs.

The process begins with donated fabric and clothing which is sorted by color and cut into strips. These strips are then woven by hand onto vertically hung square-mesh netting such as safety netting or repurposed volleyball and soccer nets. The finished nets are then sent off to the troops, who commission them to address specific wartime needs.

I follow several Polish textile-art pages on social media, and happened upon some images of students and faculty at the Academy of Fine Arts in Łódź weaving nets immediately after the start of the war. I was struck by the way that these art spaces, students, and materials were mobilized into the war effort. The division between textile art and craft—the evolution of fiber art from domestic textiles and other useful, hand-crafted forms—has been a great interest in academic circles, but the conversation and practice rarely runs backwards.

It is unusual for art students to spend their studio days weaving massive industrial cloths by hand, but in this case, formal skills and equipment were suddenly repurposed from the world of experimentation and study in service of something physically necessary and useful. The medium and practice was reverse-engineered to allow for this craft-based, purpose-driven production.

In the 2022/2023 academic year I was making work at the Academy of Fine Arts in Łódż, a post-industrial city with a deep connection to textiles, having been a major producer of commercial and industrial fabrics for the USSR through the 1980s. I was there through a Fulbright Grant, researching the Polish School of Textiles from the 1960-70s.

The radicality of Polish textiles in that era, exemplified in the work of Magdalena Abakanowicz, also came in response to war. This movement largely concerned gender, form, and scale. In the Polish School of Textile Art, a number of female artists, working with what little was available after the Second World War, combined innovative materials and techniques to revolutionize the field of fiber art.2 Materials such as sisal, rope, and twine were worked using intuitive, textural hand-weaving at monumental scale. Previous to this shift, fine art tapestry had been a male-dominated field which essentially reproduced the paintings of famous artists into woven form using a “cartoon” stencil-like reproduction technique. After the shock of the first Lausanne International Biennale of Tapestry in 1962, where the first of this new style of work debuted, the field evolved into what many now associate with contemporary fiber art, wherein original compositions often present in some combination of woven, imperfect, experimental, or textural, and are made or shown in a vertical orientation. The Polish School of Textiles evolved against a background of Soviet occupation and status-quo, working within these systems to radically change the field of textile art.

It is unusual for art students to spend their studio days weaving massive industrial cloths by hand, but in this case, formal skills and equipment were suddenly repurposed from the world of experimentation and study in service of something physically necessary and useful. The medium and practice was reverse-engineered to allow for this craft-based, purpose-driven production.

In the 2022/2023 academic year I was making work at the Academy of Fine Arts in Łódż, a post-industrial city with a deep connection to textiles, having been a major producer of commercial and industrial fabrics for the USSR through the 1980s. I was there through a Fulbright Grant, researching the Polish School of Textiles from the 1960-70s.

The radicality of Polish textiles in that era, exemplified in the work of Magdalena Abakanowicz, also came in response to war. This movement largely concerned gender, form, and scale. In the Polish School of Textile Art, a number of female artists, working with what little was available after the Second World War, combined innovative materials and techniques to revolutionize the field of fiber art.2 Materials such as sisal, rope, and twine were worked using intuitive, textural hand-weaving at monumental scale. Previous to this shift, fine art tapestry had been a male-dominated field which essentially reproduced the paintings of famous artists into woven form using a “cartoon” stencil-like reproduction technique. After the shock of the first Lausanne International Biennale of Tapestry in 1962, where the first of this new style of work debuted, the field evolved into what many now associate with contemporary fiber art, wherein original compositions often present in some combination of woven, imperfect, experimental, or textural, and are made or shown in a vertical orientation. The Polish School of Textiles evolved against a background of Soviet occupation and status-quo, working within these systems to radically change the field of textile art.

From top left: 1. The first Lausanne Biennale in 1962 with Abakanowicz’s Composition of White Forms shown on the right, Alice Pauli archives 2. Abakanowicz with her work, 1962. Photo: Francoise Rapin. 3. Abakanowicz’s Abakan Yellow, 1967 in the Tate Modern’s retrospective Every Tangle of Thread and Rope, 2023. 4. Abakanaowicz with her students in the textile studio at the University of the Arts, Poznań. Photo courtesy of Dr. Anna Goebel.

The weaving of war nets in Łódż started when lecturers from the Lviv National Academy of Art sent photos to colleagues at the Academy of Fine Arts with the request: “We sew masking nets for Ukrainian civilians, we run out of material. Help.”3 Volunteers initially wove nets intended to hide civilians and the entrances to bomb shelters from Russian bombardment in Lviv. By the time I arrived in the Fall of 2022, the effort was devoted to fulfilling production requests for the military—soldiers needed specific sizes of nets to hide equipment and trenches from drone attacks, and to serve as tents.

Documentation of a student in the main weaving studio at the Łódż Academy of Fine Arts, working on war nets for the Ukrainian war front in March, 2022. Photo: Marcin Stępień for Agencja Wyborcza.pl

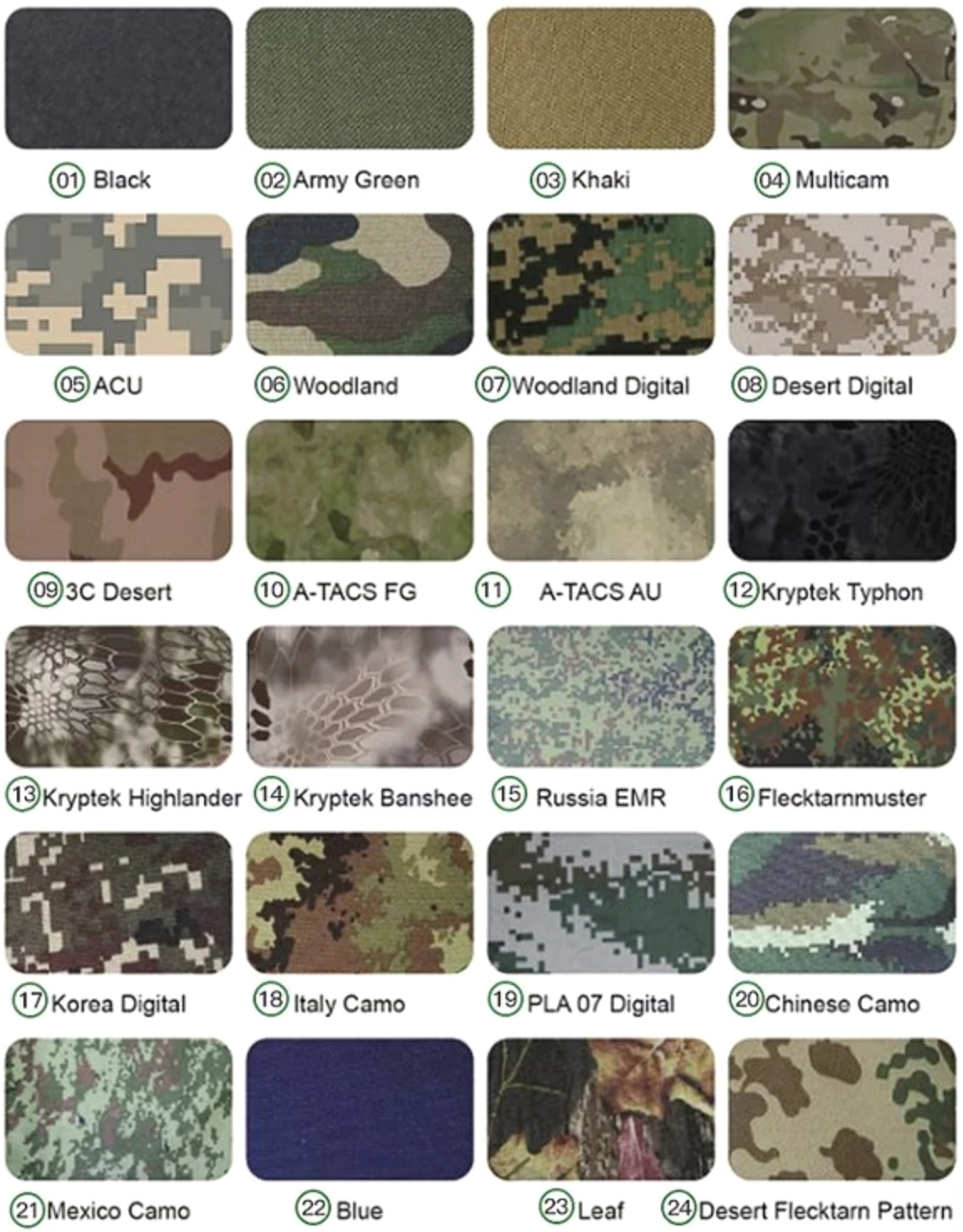

Aside from variations in size, different colors suit wilderness and urban settings, and the nets’ tone shifts to better reflect the seasons (more grey for winter, brown for fall). However, since the Ukrainian nets rely on material donations, almost everything that is not too bright or shiny is eventually woven in. The most important things are to weave erratically to avoid making patterns, and not to leave any gaps in the cloth.

There are many variations of camouflage developed by the world’s nations based on differences in native flora, topography, and other natural features.4 The most used colors in the Ukrainian war nets are found in the traditional American “woodland” and “multicam” camouflage—earth tones, neutrals, and greens. Image courtesy of Camopedia

The LOOK Gallery weaving venue, on the campus at the Academy of Fine Arts in Łódż, Poland. April, 2023

The LOOK Gallery weaving venue, on the campus at the Academy of Fine Arts in Łódż, Poland. April, 2023After the initial wave of support, daily net production at the Academy of Fine Arts in Łódź was mostly carried out by a handful of Ukrainian refugees and staff at LOOK Gallery on campus. However, the venue was open to volunteers during regular business hours, and newcomers were invited to join in at any time. Several weaving workshops were also offered during the European Textile Network Conference (ETN) which held its annual meeting in Łódz in March of 2023. Many conference goers were, like me, academics and artists from Western nations, eager for the chance to participate in a fight that they supported, but from which they were personally far removed. The nets are an outlet and a way to show solidarity against occupation. They provided an opportunity to help the Ukrainian effort in an immediate, physical way.

I usually found my way to the weaving gallery when I knew no one else would be present, as I preferred weaving alone to the performative aspect I associated with weaving in a group (particularly as a visiting outsider from the US). Tea and sweets were always on hand, as were the precut strips of fabric. In-progress nets were held taut by the weight of big bottles of water; shifting bundles of donated materials and completed nets filled the corners of the room; even the boxes of sweets on the table all reflected the banality and dailiness of the war.

I usually found my way to the weaving gallery when I knew no one else would be present, as I preferred weaving alone to the performative aspect I associated with weaving in a group (particularly as a visiting outsider from the US). Tea and sweets were always on hand, as were the precut strips of fabric. In-progress nets were held taut by the weight of big bottles of water; shifting bundles of donated materials and completed nets filled the corners of the room; even the boxes of sweets on the table all reflected the banality and dailiness of the war.

Bundles of completed nets ready to be shipped to the front.

Camouflage is usually synthetic and machine-made, but intended to mimic the patterns, colors and seasons of the natural world. And like nature it can be cruel; used to hide and attack, its associations with conflict are clear. Through the production of the nets, however, a camouflage object acquires new associations—of collectivity and solidarity against violence and occupation. Like the reverse-engineering of textile art into a purpose-driven form in the Academy, the reverse-engineering of camo from industrial and detached to hand-made and personal is unexpected and remarkable.

Ukrainian women weaving camouflage war nets in the basement of a museum in Kyiv. Some of the volunteers here have been weaving nets for the front since 2014. Screengrab courtesy of The Washington Post, youtube

As of this writing, international weaving efforts in support of Ukraine have mostly concluded. The women in the Donbas region of Ukraine, however, have been making camo nets for 10 years, resisting occupation through weaving by hand. These nets symbolize the potential of participation and collective action around a shared goal and values. Their production has brought an inherent, physical radicality into unexpected spaces and contexts.

1 Nadija Lystopad https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iK9rbyMX5q0

2 Marta Kowalewska, Michał Jachuła & Irena Huml (2018) The Polish School of Textile Art, TEXTILE: A Journal of Cloth and Culture, 16:4, 412-419, DOI: 10.1080/14759756.2018.1447074

3 “Artyści na pomoc mieszkańcom Lwowa. Na ASP w Łodzi studenci i wykładowcy tkają siatki maskujące”. 04.03.2022, Wyborcza.pl / Łódż. By Sandra Kmieciak. Translation by DeepL.

4 Camopedia: Camouflage patterns by region, country, and use

See comment by Tim Kerk for “woodland” and “Multicam” examples

Further Viewing:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pYlaqxtNQho

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rLtc1WxNlwQ

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dkSzLbeoFGE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iK9rbyMX5q0

Paulina Berczynski is a Berlin-based Polish-American artist, and co-founder of Feral Fabric. In her studio work, workshops, and site-specific projects, she often employs fabric collage to facilitate exchange between people from different backgrounds and communities. She is influenced by traditional forms such as quilts and domestic crafts, movements for social justice, utopianism (with all of its personal and cultural complications), and the aesthetics and resistance of occupied 1970-80s Poland.

Paulina’s work is informed by her past as a child immigrant and refugee who moved many times through different languages and socio-economic realities. She is a 2022 recipient of Southern Exposure’s Alternative Exposure grant for Feral Fabric Journal, and a 2023 resident at Prelinger Library, where she focused on Utopian communities in California. In April 2024 she will be an Artist in Residence in Zusa's What's Next program, exploring new ideas of solidarity in Europe.